“For eight years in a row, an international survey of nearly 300 cities has named Hong Kong the world’s least affordable housing market.”

“A government task force is considering a wide range of options to make better use of available land. Architects and developers have also put forward some novel proposals, ranging from the quirky to the audacious. While some of the ideas may be repackaged versions of the cramped spaces the city has long known, others could reshape the future of housing in Hong Kong. Here are some of the ideas.”

As the Bay Area scrambles to find housing for its growing population, developers are running into another kind of shortage: There aren’t enough construction workers to build the homes the region needs.

Builders throughout the area say they are struggling to recruit skilled laborers. Some bring in employees from Southern California or even Seattle, putting them up in hotels. Others hire workers from the Central Valley who spend hours driving to job sites in the wee hours of the morning only to arrive exhausted, forced to squeeze in quick naps before the workday starts.

The challenge of finding workers only exacerbates the Bay Area’s housing shortage. Despite a dramatic increase in permits for residential construction since 2009, construction jobs have increased at less than one tenth the pace of permits. As a result, wages and the overall cost of building are increasing, forcing some developers to delay projects or, in some cases, not build at all.

![]()

![]() California, many say, is the future. A center for creative industries and new technology—look at its impressive rollout of electric vehicles and autonomous cars—it’s also a diverse state, pushing progressive policies that could be models for the rest of the country.

California, many say, is the future. A center for creative industries and new technology—look at its impressive rollout of electric vehicles and autonomous cars—it’s also a diverse state, pushing progressive policies that could be models for the rest of the country.

And people are leaving in droves for opportunities elsewhere.

The actual migration patterns in California aren’t quite as bad as that sounds—at least not yet. But a recent report by the California Legislative Analyst’s office looking at domestic migration patterns shows that cracks continue to form in the state’s bright facade. Between 2007 and 2016, a million more people have left the state than have moved in from other states.

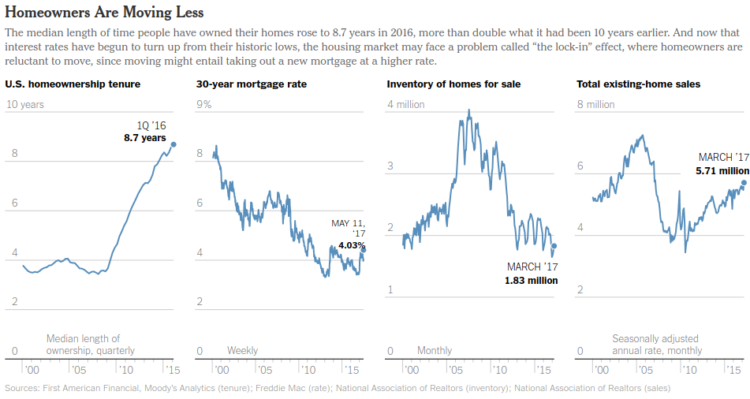

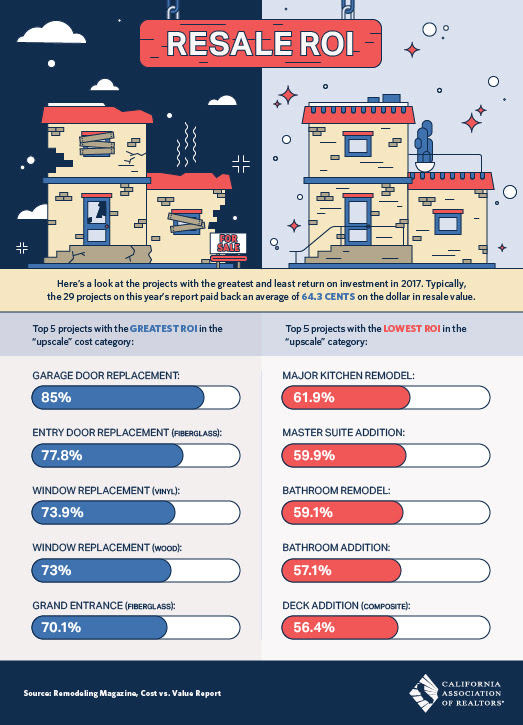

For much of last year, Greg Rubin was looking to buy a bigger house. He has been in the same two-bedroom home for 17 years and hoped to upgrade to a place with a guest room, a home office and a workshop for his guitars, radio-controlled planes and gardening equipment.

For much of last year, Greg Rubin was looking to buy a bigger house. He has been in the same two-bedroom home for 17 years and hoped to upgrade to a place with a guest room, a home office and a workshop for his guitars, radio-controlled planes and gardening equipment.

This year, Mr. Rubin has a new plan. He stopped looking and embarked on an ambitious renovation project that will begin with a new kitchen and end with a workshop for all the man toys.

“My girlfriend would like to get a larger house, but right now, I’m staying put,” said Mr. Rubin, who lives in Escondido, Calif., and owns a landscaping firm called California’s Own Native Landscape Design.

Mr. Rubin is the face of what appears to be a new normal in the real estate business: Homeowners are moving less, creating a drag on the economy, fewer commissions for real estate brokers and a brutally competitive market for first-time home shoppers who cannot find much for sale and are likely to be disappointed during real estate’s spring selling season.

When cities like Oakland prohibit new apartments and condos in wealthy neighborhoods, low-income areas pay the price.

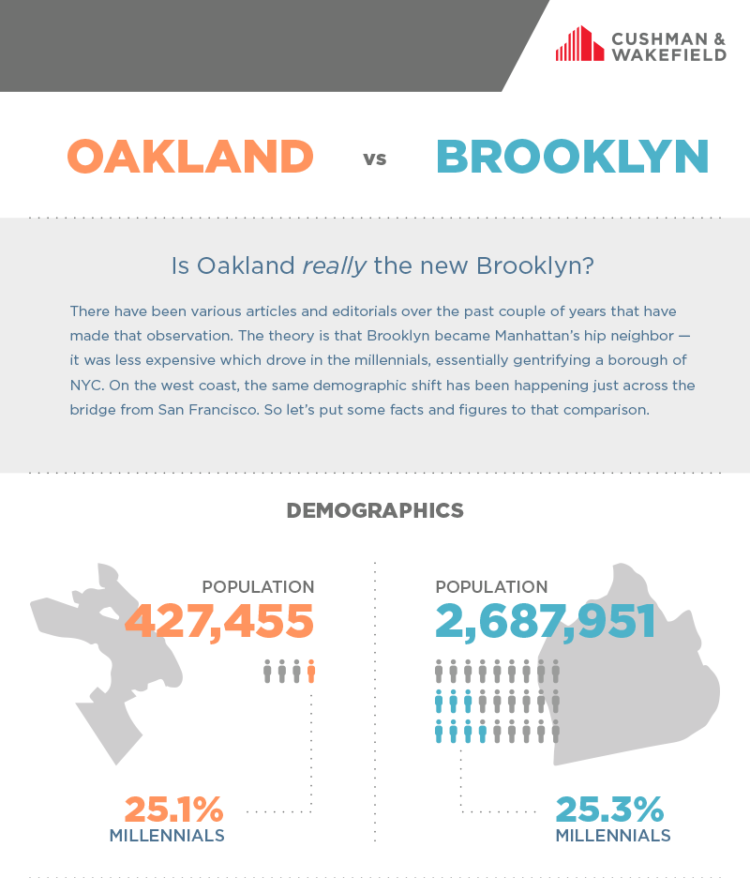

When Victoria Fierce arrived in the Bay Area three years ago, she decided to look for a place to live in North Oakland’s Rockridge district. She had scored a job at a tech startup in San Francisco and was attracted to Rockridge because it has a BART station and seemed like a transit-oriented, walkable neighborhood. But she quickly realized that apartments are scarce in Rockridge and the nearby Temescal district and that rents are astronomically high.

“When I first move out here,” she said, “I looked at Rockridge, and thought, ‘Wow, this is so great. … I wish I could afford to live here.’”

Fierce relocated to Oakland from Akron, Ohio, and ultimately landed in downtown. Although she loves living here, she says she sometimes doesn’t feel welcome. She and other millennials who moved to Oakland during the tech boom have been blamed for gentrifying traditionally low-income areas of downtown, Uptown, and West Oakland. Some city residents have derided the newcomers, alleging that they’re responsible for soaring rent and housing prices and the displacement of low-income people of color. Fierce, who is transgender, said she and her friends have been called “gentrifiers” and “techie scum” among other names.

But Fierce and her friends don’t scare easily, and they’re fighting back. They formed East Bay Forward, a group that champions new housing in Oakland, Berkeley, Alameda, and other urban areas, especially along transit lines. They consider themselves to be urbanists, or YIMBYs (for Yes In My Backyard), and they attend city council and planning commission meetings in support of dense housing developments and high-rises, while publicly calling out the NIMBYs (Not In My Backyard) who oppose them.

The for-rent ads in the San Francisco Chronicle on Sunday, April 2, 1961, sound dreamy:

Luxurious spacious 4 rooms. Many walk-in closets. All Utilities included. $155 a month in the Marina.

Deluxe 3. Garbage disposal, wall-to-wall carpet. Garage included. $125 and up in Pacific Heights.

Spectacular Marine view. 1-bedroom, sun deck. $175 on Telegraph Hill.

Those were the good old days, right?

In fact, in the early 1960s, rents in San Francisco were rising by an average of about 6.6 percent each year. As it turns out, that’s the same annual rate they would later rise in the 1970s, and in the late 1990s, and in the mid-2000s. It’s the rate they’re rising today.

How many units would we need to build in order to slow or reverse the rent increases? You can find the whole article on Wonkblog.